In an interview with Grant Sanderson (3Blue1Brown), Dwarkesh asked why so much of math discovery has been recent. If Mathematics is made of axioms and self-constructed symbols, shouldn’t something fundamental like Information Theory be discovered sooner than the 20th century?

In response, Grant posited that much of Mathematics was developed in tandem with scientific and technological development at the time. In theory, someone could wake up one day and think of the equations independently of the world. In practice, it was the scientific discoveries like communication devices that pulled mathematicians into developing theories underlying the process.

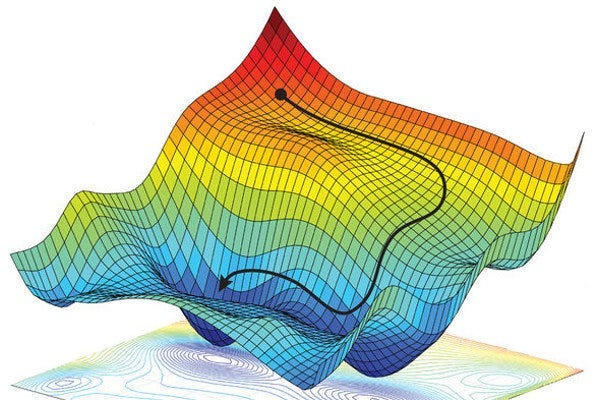

In other words, because the search space is so large, navigating through it requires a combination of motivating questions, heuristics, guidance, free-form exploration - what we call taste.

*

In 1997 the chess engine Deep Blue beat grandmaster Garry Kasparov for the first time. It made waves across the world, but the underlying reasoning is simple: we got better at compute. Whereas the human brain with its limited capacity relies on pattern-matching, a computer engine can search through the possibility space many layers deeper - calculating the probability at each step more accurately than any human could. What we consider a ‘novel’ move in chess is simply a move that maximizes probability of winning in an unforeseen way, and this is reducible to a number that an engine can calculate.

This was harder in larger search space, like Go where the board was 19x19 instead of 8x8, but that changed in 2015 where AlphaGo beat humans for the first time. It was harder still in even larger search space, like the entire English corpus, but that changed in 2022 with the introduction of GPT-3.

*

It is easy to pinpoint the boundaries for games like chess or Go, or the grammatical rules underlying the English language. But most search spaces are not like that - they are plagued with blurry-defined boundaries and expected value functions. Like, what makes a good conversation and how do you measure that? You can point to some indicators: the content of the strings of words, the emotional valence counted through laughter or head nods, the interlocutors’ facial expressions? Creating such a convo, as any charismatic person would tell you, is more art than science - it’s a combination of combing through their own world for relevant but divergent response and asking good questions and being insanely responsive and a few more tacit things that are blurry to define. In theory, you can have an LLM replicate that by making explicitly clear the end states and tracking all variables like heartbeat and hormonal fluctuations, but as of now, the search space is too large, the variables too many, and so humans triumph.

I’ve been using Claude as my placeholder therapist for a while. I find that Claude is probably the 80th percentile therapist, but the most life-affirming conversations still happen when I’m talking to someone in real life. What AI is good at: following the frame; what humans are good at: breaking it. Claude is excellent at summarizing responses, applying frameworks I’ve articulated in explicit situations, navigating through the structures I’ve set up. But when I talk to a close friend, they would uncover an emotional truth through the tone of my voice, ask a question I’ve not thought of, or draw out a story from their own world that maps out to mine. In other words, they expand the map of my emotional landscape, illuminating the internal search space a bit further.

LLMs are great at optimizations in search spaces that are already mapped out. And obviously, there are lots of undiscovered heuristics in a space that is already known, ways to navigate more efficiently. But in domains where the search space is too large and full of opaque variables and hard-to-define objectives, in the real world, we still rely on human intuition, human taste, to guide the way.

*

How does one cultivate taste? Or, to reframe it another way, how does one find heuristics in fuzzy-defined ill-illuminated search spaces?

If the objective is clearly defined, one can do something like MrBeast - simply consume as much raw data as possible. MrBeast credited his success to locking himself in a room since he was 13 and watching all the YouTube videos with the highest number of views for hours on end. Through millions of minutes, his mind started churning and noticing patterns: thumbnails should be this way, title that way, in the first minute you need to do this. In cases like these though, there is a clear indicator for the objective - number of views. It is also easily measurable, but easily replicated by AI (lots of YouTube thumbnails and titles are already AI-generated). But taste matters most in fuzzy-defined space. What other options do we have?

A thing that seems unique to humans is - well, people. A Nobel laureate is 3 times more likely to mentor another Nobel laureate. Throughout history there are lambent sparks of milieu gathering in a single physical location - 15th century Florence art scene, 20th century Paris literary scene, Bell Labs, the Manhattan Project. Other people, in the form of mentors or peers, have a memetic effect, diffusing good tastes explicitly or implicitly.

Finally, what we call taste has a physical embodiment. It manifests in curiosity. What we are drawn to, what we are curious of, is like a metal detector for unexplored landscape. Curiosity nudges us towards the edge of our maps, then compels us to turn over stones and look into caves of our minds and of the world. Taste guides curiosity towards interestingness, and in return curiosity expands the boundaries of taste. Let us wander.

Thanks to Trang Doan for draft feedback & accountability, and Henrik Karlsson for the original email thread that sparks this essay.

So sooo adore this post. I've been thinking a lot how to navigate the use of AI in a world where there is so much anxiety of it overtaking our creative works. But taste and curiosity is a distinctly human thing with an internal compass I would be impressed if mathematicians of the future could replicate.

I love this: “But when I talk to a close friend, they would uncover an emotional truth through the tone of my voice, ask a question I’ve not thought of, or draw out a story from their own world that maps out to mine. In other words, they expand the map of my emotional landscape, illuminating the internal search space a bit further.”