I started this book because of an argument with an ex.

I had just finished The timeless way of building at the time, and was in love with the Dao, a natural harmony of the world. It fitted my worldview so well - an idealistic way of being human, of the underlying forces that govern everyone. When I brought that up in a conversation, he immediately retaliated, ‘Are humans really that similar? Don’t we have research on vast cultural differences, and wouldn’t that mean there are no one type of humans?’ I thought that was inaccurate - we had similar biology, genetic components and neurological wiring, surely we cannot be that different from each other. A debate ensued, but neither of us knew enough about the subject to come to any meaningful conclusion1.

Anyways, I was annoyed by this conversation and wanted to be right. That same week I picked up The WEIRDest people in the world by Joseph Henrich (h/t Dwarkesh’s podcast) and started reading.

Welp, I’m begrudgingly reporting back that my ex was right. Well, sort of. Henrich’s main argument is that a specific group of humans, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD), are especially peculiar psychologically, and it is that unique psychology that lays the foundation for the institutions and prosperity that we see today.

i. Humans are powerful not because of our intelligence but because of our culture

To understand Henrich’s argument is to see how the “nature” vs “nurture” debate misses the point - there is not just what is “in our genes” vs “in our culture”. Instead, it is a positive feedback loop in which our genes condition us to learn from our culture, and our culture in turn rewires our brains and alters our biology.

A chimpanzee can survive without copying its mates; a baby cannot survive on its own in the wild. Instead, it survives through thousands of guided learning, copying from its elders.

Crucially, these genetically evolved learning abilities aren’t simply downloading a cultural software package into our innate neurological hardware. Instead, culture rewires our brains and alters our biology - it renovates the firmware.

And crucially - the cumulative effect of culture often happens without people understanding what they do. An example from the book was how Congo Basin hunter-gatherers made a deadly arrow poison, which was an elaborate process that combined 10 different plant species and a sequence of elaborate steps (including a dead monkey). But nobody in the clan knows what each step of the process does. In other words, there is no wired understanding of the deadly arrow poison wired in the genes of each Congo Basin hunter-gatherer. Instead, they each adopt a brain that can absorb these cultural instincts, and over time as each generation transmit some wisdom, and others get replaced, updated, and tweaked, the result creates the world’s most deadly poisonous weapon.

More from Henrich:

To thrive in this world, natural selection favored expanding brains that were increasingly capable of acquiring, storing, organizing and retransmitting valuable cultural information. […] We thus evolved as a species to put faith in the accumulated wisdom of our forebearers, and this ‘faith instinct’ is at the core of our species success.

But it also means that what makes a culture good is not set in stone. In fact, culture undergoes evolution the same way genes do - society with better culture outperforms those with worse culture, through warfare or voluntary adoption, which then gets copied and adopted and spreads overtime. Groups that are better at coordinating, for instance, can more easily win wars, attract immigrants, or grow economically.

ii. WEIRD culture dominates … through Christian monogamous nuclear families??

WEIRD culture, or what we normally associate with ‘the West’, is deeply tied with the spread of Catholicism (and Christianity). Henrich’s book argues that to understand how WEIRD culture evolved and dominated, we need to understand the spread of Christianity.

The pre-Christian world was based on intense kinship networks of clans. You would marry your third cousins, live in multi-generational communities and abide strictly by elder laws, if you were a rich man you would have multiple wives and if you were a woman you would most likely be a second or a third wife of these men. You had your in-group which you are deeply loyal to, while being completely distrustful of strangers and anyone in the out-groups.

Christianity was radical at its existence because it promoted the idea of spiritual kinship, that there exists a ‘family of God’ that cut through blood lines. Thus people were encouraged to separate from their extended families to find fellow Christians, and settle based on this religious beliefs, to find their ‘brothers and sisters in Christ’. Marriage is also now based on consent of the couple, not a clan contract. The Church over hundreds of years also started to prohibit cousin marriages, up to 6th cousins, and encouraged newly wed couples to set up independent households away from their extended families.

Then there was monogamy. Prior to Christianity, polygyny was most common - 1 man had multiple wives. 90% of hunter-gatherer populations and 85% of agricultural societies had polygynous marriage. But as a result, many men that remain unmarried. The illustration below showed this effect: even when only the top 20% of men are polygynous, and have a maximum of 4 wives, the effect can mean that up to 40% of men would be single. For these men, often the only way to ‘increase their status’ so to speak was through violent and illegal activities like robbery and murder. In comparison, married men are more likely to co-operate and play positive-sum games.

The Christian doctrine was basically the first to promote this ideal marriage of lifelong, exclusive bond between two individuals. The Church did this both through religion - promoting the ideal Christian marriage that would lead to eternal afterlife. But also through code of law - banning polygyny. allowing for only monogamous, Church-sanctioned unions. Crucially, even the elites were subjected to the same rules. This meant that if kings and lords have mistresses, their children could not inherit land or title. By contrast, in imperial China or Islam, polygyny was still part of the legal code (e.g. Islam permits up to 4 wives, but illegitimate children cannot inherit properties).

To emphasize how weird this is - no group-living primates besides human have monogamous marriages. Most of our ancestors were polygynous. Kings and emperors in the past often had hundreds, sometimes thousands of wives. Without a certain set of cultural institution (in this case, Christianity), our evolved psychological biases would not have created the monogamous “naturally”.

But a society with more monogamous marriage was one that ultimately became more stable and cooperative, with greater economic and social results.

The combined effect of 1/ banning cousin marriages, and 2/ monogamous marriages was a society based on weak ties of voluntary associations, rather than strong ties of blood-based kinship. Because of nuclear families, households could move away from their blood ties more easily and set up residences in places with more commerce. This in turn created psychological changes that ended up persisting over many generations - one that rewards pro-sociality towards strangers, at the expense of reducing closeness towards in-groups.

While the urban centers of 11th-century Europe may have superficially looked like puny versions of those in China or the Islamic world, they were actually a newly emerging form of social and political organizations ultimately rooted in, and arising from, a different cultural psychology and family organization. […] Small families with greater residential and relational mobility would have nurtured greater psychological individualism, more analytic thinking, less devotion to tradition, stronger desire to expand one’s social network, and greater motivations for equality over relational loyalty.

Over hundred of years, Europe started to urbanize more rapidly as nuclear families amalgamated to set up their own shops and guilds, and over time, norms, laws and formal institutions. As people congregated in towns and exchanged goods and ideas, the Golden Age of Europe began. Larger groups of people allowed for specialization and also higher reliance on formal institution and contracts, which further reinforced WEIRD psychology. People increasingly valued impartiality and normative market forces, which in turn influenced culture and individual psychology. Circa 1300s, these dense, self-governing towns started a flywheel of innovation, scientific progress and market innovation, which slowly transformed the world as we know it today.

iii. i’m so glad i’m not in a harem

Proposed explanations for “Why Europe?” emphasize the development of representative governments, the rise of impersonal commerce, the discovery of the Americas, … but what’s missing is an understanding of the psychological differences that began developing in some European populations in the wake of the Church’s dissolution of Europe’s kin-based institutions.

Before reading, I had a pretty idealistic image of non-WEIRD culture, including where I’m from (Vietnam). We are warm people who care a lot about community and tradition, a healthy respect for elders, with strong obligation and duty towards our family. By contrast, WEIRD cultures like the US feel cold, distant, and lonely.

But reading this book makes me realize how much I’m indexing on the present, while missing major contexts of the past. For instance, Vietnam only explicitly banned child marriage, forced marriage and polygyny in 1959. How recent is that!? Most of what I take for granted are direct legacies of WEIRD institutions and cultural influences.

Non-WEIRD populations excel at, what Henrich calls, “a warm hug”: thick obligations, emotional safety nets, deep loyalty towards familial ties. And I don’t want to dismiss this as a small thing: research has shown that the biggest predictor of happiness for people is the strength of their close-tie relationships. WEIRD culture often gives up the very thing that make them happy and struggle with hyper-individualism a lot more than other culture.

But they also have a more egalitarian outlook for the world, as compared to non-WEIRD culture:

[Non-WEIRD people] tend not to be “approach-oriented” aimed at starting new relationships and meeting strangers. Instead, people become “avoidance-oriented” to minimize their chances of appearing deviant, creating disharmony, or bringing shame to themselves and others.

In societies with weak kinship ties, strangers feel entitled to step in and police bad behaviour: tripping a purse-snatcher, or pulling an unknown husband off a wife he’s beating. By contrast, in places organized around powerful clans, you’d never interfere in a dispute between two strangers—you can’t be sure it isn’t clan business, and meddling could trigger violent retaliation.

This egalitarian fairness is a psychological contribution from WEIRD culture. Very few Vietnamese I know, for instance, would understand that some people would not eat meat i.e. sacrifice their own wellbeing ‘for the animals’, but many Westerners do commit to veganism based purely on philosophy.

And it’s not just my personal experience, research supports it too: in an experiment researchers ask participants to play a “Dictator Game”: they are given 1 day of local’s wage, and decides how much to give it to a stranger. They found that WEIRD cultures (e.g. the US) give closest to 50% of the wage to the stranger (the “fairest” offer) as compared to hunter-gatherers societies.

In a separate example, each participants get 20 tokens and secretly chooses how many to put into a common pot. Tokens in the pots are multiplied and split evenly among 4 group members. After seeing everyone’s contributions, each player can spend 1 token to deduct 3 tokens from any teammate (“punishment” option).

Research around the world shows that, the more WEIRD a culture is, the more likely they are to punish “free-riders” (i.e. people who contribute less than their fair share). Meanwhile, non-WEIRD cultures are more likely to punish HIGH contributors (i.e. retaliate against members who make them look bad).

Our ability to be fair with strangers, as it turns out, is not innate. Rather, it’s a learned cultural set of behaviors that WEIRD culture, through both chances and evolutionary forces, bring out.

And this is a big deal! Our legal institutions, declaration of human rights, market & free trades, and social democracy are built based on the opposite of this instinct to bias the in-group! It is completely dependent on our ability to “trust” strangers and willing to play positive-sum games with them.

They also happen to be prime conditions for Scientific Revolution. Playing positive sum games mean scientists are more collaborative. Fairness and egalitarian means openness to ideas regardless of their authority and credentials. Analytical thinking brings a willingness to break things down and put up a scientific lens. These psychological marks create the flywheel of innovation.

WEIRD culture contributes to our cultural packages by imbue-ing this sense of equality and fairness which is not innate in our biological hardware. And if Henrich’s account is correct2, then this analytical and sterile culture is also one that is marching towards human progress in major ways, both economically and morally3. That deserves more acknowledgement and respect than we currently have.

And personally? I’m just glad I’m not in a harem.

Thanks to Trang, Chris, Nikita, Megan for commenting & and discussing earlier ideas and drafts with me.

to be clear we didn’t break up because of this fight (sorry ex if you’re reading this you’re being used for a clickbait opening :)))

The one qualm I have with the book is how it is light on the other way WEIRD culture conquers the world, namely through pure violence and conquest. Colonization was basically not a discussion at all; Henrich only focused on innovation and market forces. Which is fair - I do think the Scientific and Industrial Revolution has played an important role in domination of Western ideology. But there was little acknowledgement of violence, military conquest, and the more brutal parts of history. Granted, he does have a chapter on war and how war made people more religious, but this was mainly focusing on European War between 800-1200s, with much less emphasis on European colonization and conquest specifically.

Well, maybe up until 1980s/ 2010s depending on how you look. I feel like there’s 2 major trends that reverse that:

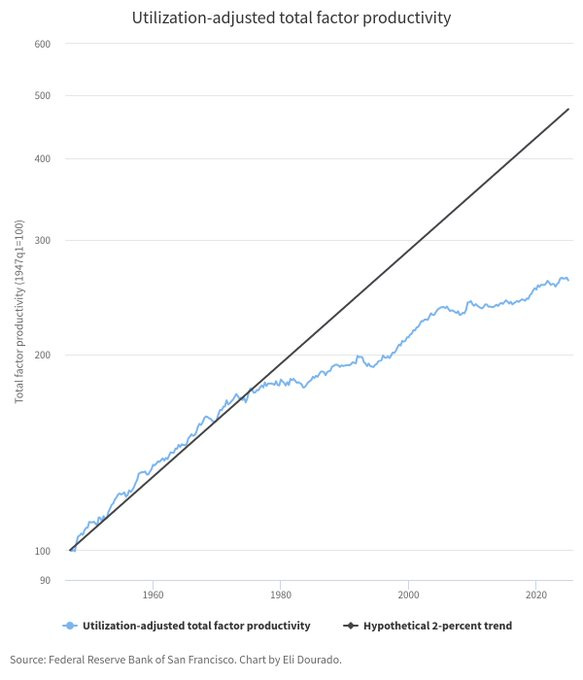

1/ the 1980s reduction of total factor productivity leads to slowdown in economic growth ie. what Tyler Cowen coined the great stagnation.

(though this is pretty US centric hmmmmm).

2/ it seems to me that the moral circle has kept expanding yet again in the early 2000s (e.g. veganism started to go mainstream) but then something happened? social media perhaps? or maybe it’s also just a downstream consequence of global macroeconomic slowdown.

all these are kind of budding thoughts tho, book/article recommendations welcome.

![The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous [Book] The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UrN0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe4d4b7a6-0d6f-4cb3-b34a-0cc43d402fe6_1707x2560.jpeg)